and he recommends this site as well.

Against Monopoly

defending the right to innovate

Monopoly corrupts. Absolute monopoly corrupts absolutely.

Copyright Notice: We don't think much of copyright, so you can do what you want with the content on this blog. Of course we are hungry for publicity, so we would be pleased if you avoided plagiarism and gave us credit for what we have written. We encourage you not to impose copyright restrictions on your "derivative" works, but we won't try to stop you. For the legally or statist minded, you can consider yourself subject to a Creative Commons Attribution License.

current posts | more recent posts | earlier posts

Rufus Pollock

[Posted at 06/15/2009 06:09 AM by David K. Levine on Blogroll  comments(0)]

comments(0)]

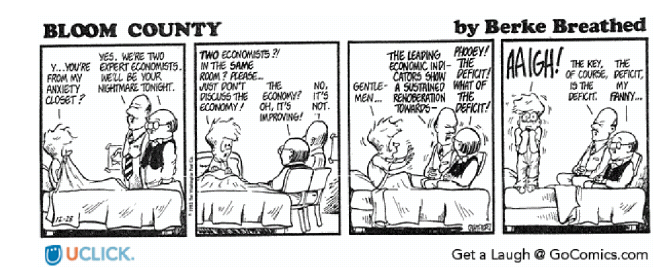

Oh those economists...

[Posted at 06/15/2009 06:00 AM by John T. Bennett on Financial Crisis  comments(0)]

comments(0)]

Issues raised by the proposed Google-Publishers scanning settlement

Riding a wave of innovation and a flood of investment money, Google emerged as the dominant internet search engine. It has gone on to provide software and on line services that are essentially free, based on advertising revenue and low costs derived from new technology. But without competition, will it remain free?

What about the libraries, only a handful of which have provided the books for Google to scan, and most of which will have to pay to offer their users access to the scanned texts. The participating libraries are mostly university supported, but the tax-supported public libraries will have to pay for access, as will individuals. Given that it is going to have a near-monopoly, what should public policy be on what they can charge?

And once again we come up with the question posed by copyright, giving publishers and owners a claim on an income stream that would not otherwise have existed. There is no clear public benefit from paying them. The owners will provide no service to receive this bonanza. Nor is the public interest protected to achieve the lowest possible price, consistent with providing the service, the marginal cost to the provider.

[Posted at 06/14/2009 06:46 PM by John Bennett on Copyright  comments(0)]

comments(0)]

Climate Change Treaties Suddenly Become Less Of A Priority Once The IP Status Quo Is Threatened

However, it should be noted that the Democratically controlled U.S. House recently voted by large margins to oppose any global climate change treaty that weakens the IP rights of American "green technology." This effectively demonstrates where the true priorities have been all along with regards to the "climate change" issue.

Details here.

(I note that the House is 'Democratically controlled' merely to help illustrate the fact that IP protection currently has well entrenched bipartisan support among the political establishment - overriding more partisan divides that might otherwise take place concerning environmental legislation. I have no doubt that this particular vote would have been the same had the Republicans been in control.)

[Posted at 06/14/2009 01:46 PM by Justin Levine on Politics and IP  comments(0)]

comments(0)]

Against Monopoly

The first one discusses a claim that the revenue lost due to file sharing amounts to a tenth of GDP. It turns out numbers were off by a decimal. And then still overinflated by assuming each download had an opportunity cost of £25. And let us forget an argument about price elasticity and the difference between a price of £25 and £0.

The second one shows that the reason music sales went down is maybe due to the fact that there are better alternatives to music, like computer games and DVDs. Sales numbers would certainly be consistent with that.

[Posted at 06/13/2009 11:07 AM by Christian Zimmermann on The Music Police  comments(1)]

comments(1)]

Sheldon Richman on Intellectual Property versus Liberty

Admirably, Richman focuses on justice rather than more utilitarian concerns such as incentive effects:

The crux of the issue is this: Do IP laws protect legitimately ownable things? One's view of the laws will proceed from one's answer to that question, and that's what I will concentrate on here. I leave for another time the issue of incentives. I do so because the justice of a claim must be decided before we consider the specific incentives and disincentives that flow from our decision.Of course, a principled focus does not mean one doesn't care about consequences; as Richman adds parenthetically, "(No, this does not make me a "nonconsequentialist." Consequences figure in our basic conception of justice.)"

Richman concludes that IP is difficult

to square with traditional property rights. When one acquires a copyright or a patent, what one really acquires is the power to stop other people from doing certain things with what is indisputably their own property. One can say that a copyright holder doesn't actually own anything but the legal authority to stop other people from using their own equipment to copy a book or CD they purchased. And one who holds a patent on the widget actually only has permission to call on the state to stop others from manufacturing and selling widgets in factories they own.Yes, this is the crux of the issue. IP amounts to trespass, or redistribution of property.

Richman quotes Thomas Jefferson to question the contention that property rules "which emerged to avert social conflict over tangible objects are also appropriate to intangible things":

If nature has made any one thing less susceptible than all others of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an idea, which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself; but the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of every one, and the receiver cannot dispossess himself of it. Its peculiar character, too, is that no one possesses the less, because every other possesses the whole of it. He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me. That ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition, seems to have been peculiarly and benevolently designed by nature, when she made them, like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density in any point, and like the air in which we breathe, move, and have our physical being, incapable of confinement or exclusive appropriation. Inventions then cannot, in nature, be a subject of property.(As an aside, notice what Jefferson writes immediately before the quoted language above:

It has been pretended by some, (and in England especially,) that inventors have a natural and exclusive right to their inventions, and not merely for their own lives, but inheritable to their heirs. But while it is a moot question whether the origin of any kind of property is derived from nature at all, it would be singular to admit a natural and even an hereditary right to inventors. It is agreed by those who have seriously considered the subject, that no individual has, of natural right, a separate property in an acre of land, for instance. By an universal law, indeed, whatever, whether fixed or movable, belongs to all men equally and in common, is the property for the moment of him who occupies it, but when he relinquishes the occupation, the property goes with it. Stable ownership is the gift of social law, and is given late in the progress of society. It would be curious then, if an idea, the fugitive fermentation of an individual brain, could, of natural right, be claimed in exclusive and stable property. [emphasis added]This argument here seems similar to the mutualist occupancy view of property. As mutualist Kevin Carson writes:

For mutualists, occupancy and use is the only legitimate standard for establishing ownership of land, regardless of how many times it has changed hands. An existing owner may transfer ownership by sale or gift; but the new owner may establish legitimate title to the land only by his own occupancy and use. A change in occupancy will amount to a change in ownership. . . . The actual occupant is considered the owner of a tract of land, and any attempt to collect rent by a self-styled ["absentee"] landlord is regarded as a violent invasion of the possessor's absolute right of property. [emphasis added]Thus, for mutualism, the "actual occupant" is the "owner"; the "possessor" has the right of property. If a homesteader of land stops personally using or occupying it, he loses his ownership. Carson thinks this is compatible with libertarianism: here he writes "[A]ll property rights theories, including Lockean, make provision for adverse possession and constructive abandonment of property. They differ only in degree, rather than kind: in the "stickiness" of property. . . . There is a large element of convention in any property rights system Georgist, mutualist, and both proviso and nonproviso Lockeanism in determining what constitutes transfer and abandonment."

I have a forthcoming criticism of Carson's notion that mutualist occupancy is a type of libertarianism; I believe it is antithetical to libertarianism--libertarianism is Lockean. But suffice it to say for now that for an anti-mutualist libertarian, Jefferson's comments above at first glance seem uncomfortbly close to mutualism. However, I think Jefferson's comments here are not really so bad, for two reasons. First, I think Jefferson was trying to make even the argument for normal property seem a bit weak, so that IP seems even weaker by contrast. Second, he only denies that there is a natural right to hold property beyond occupancy--but he is not opposed to property being owned beyond occupancy, at least in an advanced society, unlike mutualists who think occupancy is a requirement even in mutuatopia.)

Back to Richman. He has a section dealing with a crucial mistake made by many proponents of IP: their explicit, or implicit, notion that creation is a source of ownership. Why do "so many advocates of freedom" support IP, even though it amounts to applying rules applicable to scarce, tangible resources, to non-scarce, intangible ideas where no conflict is possible?

A key reason is the importance attached to the act of creation. If someone writes or composes an original work or invents something new, the argument goes, he or she should own it because it would not have existed without the creator. I submit, however, that as important as creativity is to human flourishing, it is not the source of ownership of produced goods.(Richman is right on. I've written on this exact issue before: see Against Intellectual Property, pp. 36 et seq.; Libertarian Creationism; Rethinking IP Completely; and my ASC talk and related material linked here.) I like Richman's insight here that creation is not the source of ownership; rather, that the source of ownership is "Prior ownership of the inputs through purchase, gift, or original appropriation." In this connection, as I noted in Objectivist Law Prof Mossoff on Copyright; or, the Misuse of Labor, Value, and Creation Metaphors, Hans-Hermann Hoppe writes in his classic article Banking, Nation States and International Politics: A Sociological Reconstruction of the Present Economic Order:So what is the source? Prior ownership of the inputs through purchase, gift, or original appropriation. This is sufficient to establish ownership of the output. Ideas contribute no necessary additional factor. If I build a model airplane out of wood and glue, I own it not because of any idea in my head, but because I owned the wood, the glue, and myself.

One can acquire and increase wealth either through homesteading, production and contractual exchange, or by expropriating and exploiting homesteaders, producers, or contractual exchangers. There are no other ways.Note that Hoppe here acknowledges that "production" is a means of gaining "wealth". But this does not mean that creation is an independent source of ownership or rights--production is not the creation of new matter; it is the transformation of things from one form to another; things one necessarily already owns. Therefore, the resulting more valuable finished products--the results of one's labor applied to one's property--give the owner greater wealth, but not additional property rights. If I carve a statue out of my stone, I already owned the stone, so I naturally own the resulting statue; what has changed is that I have transformed my property into a new configuration that is worth more to me, and possibly to others. (This is discussed further in Owning Thoughts and Labor.) (Similarly, if two people trade goods, each is now better off--i.e., the trade has created wealth, without creating new things--already-owned things were what was traded.)

***

Finally--Richman also highlights Kevin Carson's view that, because of "[t]he growing importance of human capital [i.e., the ideas in people's heads], and the implosion of capital outlay costs required to enter the market," the free society and competitive economy require an end to intellectual "property." (Richman observed to me that he was impressed Prychitko had written on this back in 1991, as noted in Carson's piece.)

[Cross-posted at Mises Blog]

[Posted at 06/12/2009 09:15 AM by Stephan Kinsella on Copyright  comments(3)]

comments(3)]

All The Fashion You Can Eat

Fashion depends on a constant stream of change to get people to buy the latest in-thing. Think about the design dimensions that are possible link here. How many inches above or below the knee can a hemline be? Are they going to copyright that? Take the next step. How many inches can a skirt flair? How many pleats? How wide each pleat? How many colors? How high the waistline? I'd love to be the lawyer defending a copyright infringement case in court. Ask the plaintiff what distinguishes his design. How can he answer?

It gets only slightly better when one considers the example of pretty obvious knockoffs. But big-name fashion houses aren't going to produce them. So now we are in the realm low-end fashion. Isn't the copied better off accepting the emulation as what high-end fashion is all about? The design is obviously widely admired. The original must be worth several times what the knockoffs have to sell for. And why worry? The next season will bring a whole new set of fashions. That is the definition of fashion.

Copyrighting fashion is a contradiction in terms. It will kill innovation (and profit) in the industry. Like so much else with intellectual property protection..

[Posted at 06/11/2009 06:59 AM by John T. Bennett on Copyright Sellouts  comments(0)]

comments(0)]

French Plans To Crack Down On Internet File Sharing: Back To Square One

Details here.

A few notable quotes:

The council said the proposal was contrary to French constitutional principles, like the presumption of innocence and freedom of speech. The latter right "implies today, considering the development of the Internet, and its importance for the participation in democratic life and the expression of ideas and opinions, the online public's freedom to access these communication services," the council said.Mark Mulligan, an analyst at Forrester Research, said: "What this highlights is the danger of using legislation and the courts to further your business aims. You become a victim of the whole process."

[Posted at 06/10/2009 02:08 PM by Justin Levine on The State and IP  comments(1)]

comments(1)]

Copyright fashion? A contradiction in terms

It gets only slightly better when one considers the example of pretty obvious knockoffs. But big-name fashion houses aren't going to produce them. So now we are in the realm low-end fashion. Isn't the copied better off accepting the emulation as what high-end fashion is all about? The design is obviously widely admired. The original must be worth several times what the knockoffs have to sell for. And why worry? The next season will bring a whole new set of fashions. That is the definition of fashion.

Copyrighting fashion is a contradiction in terms. It will kill innovation (and profit) in the industry. Like so much else with intellectual property protection.

[Posted at 06/10/2009 08:24 AM by John Bennett on Copyright  comments(1)]

comments(1)]

Canada rules against business method patents

The ruling included this statement, "since patenting business methods would involve a radical departure from the traditional patent regime, and since the patentability of such methods is a highly contentious matter, clear and unequivocal legislation is required for business methods to be patentable."

The Canadian ruling comes at a time when the US Supreme Court has accepted a case on the same basic question. The Canadian ruling is important for opponents of such patents because it will be harder for the US to rule differently. I do not go into the merits of the patent as it raises all the usual questions about prior art and obviousness to which so many take exception--just not the courts and the patent owners.

[Posted at 06/09/2009 05:13 PM by John Bennett on Patents (General)  comments(2)]

comments(2)]

Most Recent Comments