|

current posts | more recent posts | earlier posts From link here

A year ago, the Oregon Department of Transportation announced it had demonstrated that a new way to pay for roads via a mileage tax and satellite technology could work.

Now Gov. Ted Kulongoski says he'd like the legislature to take the next step.

As part of a transportation-related bill he has filed for the 2009 legislative session, the governor says he plans to recommend "a path to transition away from the gas tax as the central funding source for transportation."

Let's see. There are two alternatives here for increasing revenue in the face of more fuel efficient vehicles: 1. raise the gas tax. 2. introduce a complicated vehicle tracking technology to have a mileage tax. Disadvantages of the mileage tax:

**encourages gas guzzling vehicles - check

**raises serious privacy concerns - check

**probably won't work that well - check

**reduces the user fee on heavy vehicles that impose more wear and tear on the highway - check

What are the advantages exactly?

Update: you can find a bit more information here. One possible benefit of the new system is it could be used to implement congestion charges - mileage charges that depend on traffic or time of day. However, that doesn't seem to be the plan. [Posted at 12/30/2008 01:38 PM by David K. Levine on Against Monopoly  comments(2)] comments(2)] With public libraries reeling under expanded budget cuts, Google's new deal with the publishers seems to threaten public libraries, which offer Internet service.

Karen Coyle's warning about Google's new plan is short enough that I need not summarize it. Google's response seems disingenuous.

Keep in mind that the major university libraries supplied books that were subsidized by public money.

Whatever happened to "do no harm"?

link here

[Posted at 12/29/2008 09:41 PM by Michael Perelman on Fair Use  comments(1)] comments(1)] It is bizarre that the US doesn't watch what other countries are doing to extend intellectual property rights even as it is pushing ACTA to impose our laws on other countries seeking trade deals with the US. One such story link here is this whining by a musician who advocates extending the EU copyright on music from 50 to 75 years, so performers like himself could receive more royalites. He reasons, "I feel it is unfair that it should be finished." The US constitutional standard remains that IP "should promote ... the Useful Arts". Does extending the term do that? [Posted at 12/29/2008 07:14 PM by John Bennett on IP as a Joke  comments(0)] comments(0)] Once upon a time a man appeared in a village and announced to the Villagers that he would buy monkeys for $10 each.

The villagers, seeing that there were many monkeys around, went out to the

forest and started catching them. The man bought thousands at $10 and, as supply started to diminish, the villagers stopped their effort. He next announced that he would now buy monkeys at $20 each. This renewed the efforts of the villagers and they started catching monkeys again.

Soon the supply diminished even further and people started going back to

their farms. The offer increased to $25 each and the supply of monkeys

became so scarce it was an effort to even find a monkey, let alone catch it! The man now announced that he would buy monkeys at $50 each! However, Since he had to go to the city on some business, his assistant would buy on his behalf. In the absence of the man, the assistant told the villagers: "Look at all these monkeys in the big cage that the man has already collected. I will sell them to you at $35 and when the man returns from the city, you can sell them to him for $50 each."

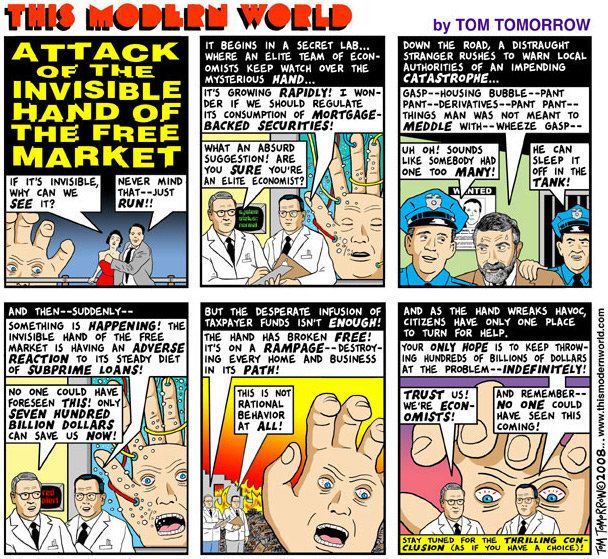

The villagers rounded up all their savings and bought all the monkeys for 700 billion dollars. They never saw the man or his assistant again, only lots and lots of monkeys! Now you have a better understanding of how the WALL STREET BAILOUT PLAN WILL WORK !!!! [Posted at 12/29/2008 05:33 PM by John Bennett on Against Monopoly  comments(0)] comments(0)] It can of course be useful to point out harmful consequences of various policies, if only to engage advocates of same on their own turf. Thus in There's No Such Thing as a Free Patent I point out that those who claim the benefits of patents outweigh the costs never seem to tally up these figures and give us the net. And indeed, whenever anyone ties to do this, they usually conclude that the patent system does more harm than good. For example, Boldrin and Levine's Against Monopoly, Bessen & Muerer's work, Julio Cole's Patents and Copyrights: Do the Benefits Exceed the Costs?, and so on (see my post, What Are the Costs of the Patent System?).

And yet, there are severe drawbacks to relying exclusively on the utilitarian approach, as I explained in my Against Intellectual Property. We need to have principled, moral reasons that can cut through the fog of inconclusive utilitarian back-and-forth. Case in point is Rosemarie Ziedonis's reply to Bessen & Muerer's On the Apparent Failure of Patents. In her civil and reasonable reply, she argues that Bessen & Muerer provide

little basis for concluding (as the authors assert) that public firms outside the chemical and pharmaceutical industries would be "better off" if patents did not exist. Public firms benefit from the patent system in numerous ways that are not captured by Bessen and Meurer's "net benefits" calculations, including through information revealed during the patenting process and through growth opportunities provided by startups. More generally, the authors are unable to observe the innovative productivity or financial performance of public firms in an alternative, nonpatent regime."

What can a utilitarian say when a critic simply replies, "but there are other benefits you are not capturing"? The strongest counter, it seems to me, is to note that the burden of proof is on the proponent of a utilitarian argument favoring a state regulation, but how do utilitarians ever know if they've taken all costs, and all benefits, into account? That's why a principled, property-rights argument is crucial.

A more complete excerpt of Ziedonis's comments follows:

A second problem with Bessen and Meurer's "better off" assertion is its implicit assumption that the private value firms reap from owning patents is equivalent to the private value those firms derive from the patent system. Here, it is important to understand what was (and was not) included in Bessen and Meurer's statistics. While the authors' "net benefits" calculations allowed public firms to be harmed by patents owned by outsiders through encounters of infringement lawsuits, they did not allow firms to reap benefits from the activities of others. Recall that only the value captured from a firm's own portfolio was captured in the authors' calculations. There are several ways in which public firms reap indirect benefits from the patent system. One is through information revealed during the patenting process (i.e., "spillovers"). In addition to enticing investment through the lure of future profits (the "reward theory" of focal attention in Bessen and Meurer's article), the patent system also aims to foster innovation through the disclosure of information about new inventions (in detailed drawings and descriptions contained in published patent documents) that otherwise might be held secret or be more difficult for outsiders to unravel.

...

Although the evidence generated from Bessen and Meurer's analysis is alarming, it provides little basis for concluding (as the authors assert) that public firms outside the chemical and pharmaceutical industries would be "better off" if patents did not exist. Public firms benefit from the patent system in numerous ways that are not captured by Bessen and Meurer's "net benefits" calculations, including through information revealed during the patenting process and through growth opportunities provided by startups. More generally, the authors are unable to observe the innovative productivity or financial performance of public firms in an alternative, nonpatent regime. Would opportunities to "outsource" R&D to more efficient performers or to profit from entrepreneurial-firm acquisitions be deleteriously affected? It is highly unlikely, of course, that the U.S. patent system will be abolished. Nonetheless, when assessing the current system's performance, these indirect effects of patents are important to consider.

[Posted at 12/20/2008 05:30 AM by Stephan Kinsella on Innovation  comments(2)] comments(2)] Baz Luhrmann has reportedly spent money acquiring the film rights to F. Scott Fitzgerald's classic novel "The Great Gatsby".

The question I have is: Why???

Gatsby is already in the public domain in his home country of Australia, Canada and other territories that use a "life, plus 50 years" copyright term.

For most other countries (including the U.S. and most of Europe), Gatsby becomes public domain in just over a year from now. Fitzgerald died in 1940. Applying the (insanely long) term of "life, plus 70 years", "Gatsby" should fall into public domain sometime in 2010.

[Am I wrong on this? I've double-checked my math and the current state of copyright law, so I don't think I am.]

Since it usually takes over a year to develop and produce a major Hollywood film, Luhrmann's adaptation of Gatsby wouldn't be released until after the original literary work falls into the public domain worldwide. Clearly it doesn't violate copyright laws to merely begin production on an adaptive work that won't actually be completed until after the public domain date. Any unpublished drafts of potential scripts and other developmental materials would certainly fall under fair use in this instance.

Luhrmann wasted his money. But then, Hollywood culture has always been overlawyered when it comes to IP rights.

For anyone who wants to make their own "Gatsby" adaptations to compete with Luhrmann and release it around the same time - have at it! May the best quality work garner the most attention. Hopefully, the competition will raise the quality of all works involved.

[UPDATE: As Gilda Radner used to say: "Never mind.

As someone who follows copyright law, I'm admittedly embarrassed in that I forgot that the "life, plus 70 rule" in the U.S. only applies to works published after 1977. Gatsby was published between 1923 and 1963, so it remains under copyright in this country for 95 years (since the copyright was presumably renewed). So Gatsby won't become public domain in the U.S. until around 2020. But the anomaly still stands that it is public domain in countries such as Canada and Australia. [Posted at 12/18/2008 02:44 PM by Justin Levine on IP in the News  comments(1)] comments(1)] It is heartening to find more and more critics of our intellectual property regime, partly as a result of growing knowledge but more importantly, the growing critical reaction to the extreme excesses of the application of the law. A new voice for me is that of Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, DC. whose book, THE CONSERVATIVE NANNY STATE;

How the Wealthy Use the Government to Stay Rich and Get Richer, is available for download on line link here under a Creative Commons license. The book is about much more than IP, as the subtitle indicates, but this review focuses on the IP issues Baker covers. He calls the chapter, "Bill Gates Welfare Mom: How Government Patent and Copyright Monopolies Enrich the Rich and Distort the Economy".

He begins by examining the richest man in the world, Bill Gates, and Microsoft, noting that it was not Gates hard work or brilliance, or the superiority of his software, but his government provided monopoly based on IP law that made him today's Croesus.

The heart of Baker's argument is that the same situation applies to patent protection in the pharmaceutical industry, and copyright protection in the entertainment industry. Vast segments of the economy are dependent on government-enforced monopolies for their profitability and survival. "In the case of prescription drugs, patent monopolies raise the average price of protected drugs by more than 200 percent, and in some cases by as much as 5,000 percent." "In the case of copyright protection, items like software and recorded music and movies that would otherwise be available at zero cost over the Internet, can instead be sold for hundreds of dollars. Clearly these forms of protection are substantial interventions in the economy."

He goes on, "The government is not obligated to award patent and copyright protection; it only makes sense if these are the best ways to promote innovation and creativity." "Copyright and patent protection support a $220 billion a year prescription drug industry, a $25 billion medical supply industry, a $12 billion recorded music industry, a $25 billion movie industry, and a $12 billion textbook industry. According to the International Intellectual Property Alliance, industries that rely heavily on copyright and patent protection accounted for $630 billion of value added in 2002, almost 6 percent of the size of the economy."

Baker's more original argument is that IP does provide an incentive for innovation as the constitution requires, but that there are less costly ways of doing so. He does so in a section titled "Efficient Mechanisms for Supporting Innovation and Creative Work".

He opens with an example, that "patent-protected brand drugs sell for more than three times the price of generic drugs that sell in a free market. This means that the country could save approximately $140 billion a year on its $220 billion annual bill for prescription drugs if the government did not provide patent protection and drugs were instead sold in a competitive market." The country could save much of that, if the research were carried on by the government, as in fact much of it already is (though to the gain of IP owner).

Baker next turns to copyright and singles out the textbook racket for close attention, arguing that revised texts are constantly being marketed with little real change in substance and at great cost. Again he would turn to the government to fund standard texts, but would allow copyrighted versions as well, which would have to find their place in a freely competitive market.

For the broader class of copyrighted material, Baker suggests a voucher system in which individuals would be given a set value of vouchers that he could credit to one or more artists. They in turn would put their creations on the internet, making them free to download. If the artist wants to copyright his work and sell it at whatever the market will bear, he could alternatively do that.

Baker ends by noting that these may not be the best alternatives to patents and copyrights, but that alternatives need to be explored.

The rest of Baker's book is ideological and will put off any who are not self identified progressives or liberals. But his basic argument is that conservatives have framed the issues in terms that they would keep the government out of much of the economy but that this is a lie. For Baker, the issue is that the government intervenes for the rich to the cost of for everyone else.

[Posted at 12/18/2008 07:33 AM by John Bennett on IP Law  comments(0)] comments(0)] [Posted at 12/16/2008 09:03 AM by John Bennett on Against Monopoly  comments(0)] comments(0)] [Posted at 12/14/2008 07:51 AM by John Bennett on Against IM  comments(1)] comments(1)] [Posted at 12/11/2008 07:45 AM by John Bennett on Against Monopoly  comments(0)] comments(0)] current posts | more recent posts | earlier posts

|